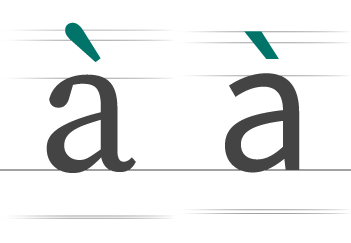

Letters

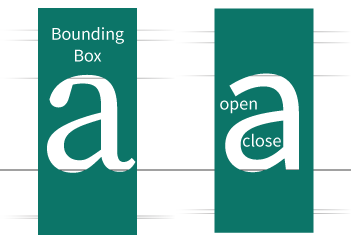

Typically, anatomy is taught referencing a serif typeface, however, both san-serif and serif typefaces share a global anatomy or skeleton. The structure of letters are used to classify and compare different typefaces. By learning what every typeface has in common it is easier to spot the differences that make classification and identification possible. Anatomy can be grouped into sections: letters, strokes, counter-space, terminals, and serifs. A letter is a character that represents the sounds used in speech; a predetermined symbol of an alphabet, therefore, letters must follow a familiar skeleton.

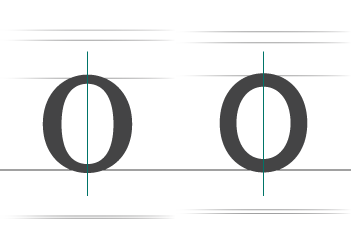

Uppercase

A letter or group of letters of the size and form generally used to begin sentences and proper nouns. Also known as “capital letters”.

Lowercase

The smaller form of letters in a typeface. They make up the bulk of written text.

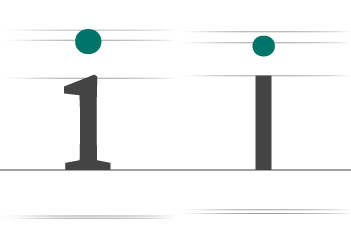

Ascender

The part of lowercase letters that extend above the x-height.

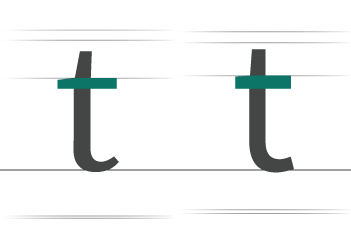

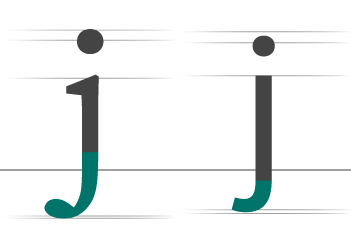

Descender

The part of lowercase letters that extends below the baseline.